Could Bipartisan Support Of The Gig Economy Finally Fix What’s Broken With Healthcare?

On June 17, 1775, after several hours of intense fighting, British soldiers drove the American militia from their position to win the Battle of Bunker Hill. While the victory came at a significant cost to the British, who at the time were among the most feared and well-trained military forces in the world, it proved to be a Pyrrhic victory.

The British may have taken control of a perceived valuable position, but it ultimately did not change the strategic dynamic; it was a hollow win, a battle against the wrong front, and one could argue the exact scenario that the US healthcare system finds itself in today.

Remembering this history lesson is critical to adequately address some of the biggest healthcare, economic, and societal challenges the country is grappling with today. It is also an important reminder for President Biden and the new Administration, specifically related to the well-intentioned but ill-fated attempt to improve healthcare access via employer-sponsored coverage for the 57 million people, or 35% of American workers, participating in the “Gig Economy”.

Unemployment due to Covid-19, along with the rise of the gig economy, is creating tension for and an opportunity to reassess the role of employers in healthcare. GETTY

A Pandemic of Inequality And A Growing Gig Economy

In addition to impacting how we live, Covid-19 has had a devastating impact on how well we live, with the pandemic only exacerbating income inequality and economic disparities. Stock prices may have reached record highs, but millions are still unemployed.

Unemployment and pandemic-related layoffs have fueled participation in the gig economy. This has benefitted many of the technology companies that facilitate the gig economy, but may exacerbate the wealth inequality between investors in those companies and the independent contractors who power them.

For example, on-demand food service platform DoorDash raised a whopping $3.4 billion in December 2020 and is valued at $61 billion as of this writing. The company’s couriers, however, only report an average salary of $11 an hour. This means a courier working 40 hours a week providing for a family of four would be below the federal poverty level, and because of their classification as independent contractors, they do not have access to employer-sponsored healthcare coverage (California gig workers notwithstanding).

Some argue that the gig economy creates further negative “spillover” effects. These negative effects include the fact that gig work should simply be called ‘precarious work’ that is not tenable for workers; that platforms such as DoorDash put a “tax” on restaurants that is destroying the food service industry; and even that the ‘gig’ lifestyle puts children of gig workers at risk.

President Biden has clearly been paying attention to the implications of the gig economy. His campaign website noted that “Employer misclassification of ‘gig economy’ workers as independent contractors deprives these workers of legally mandated benefits and protections,” with healthcare access being one of those. In addition, current legislation passed by the House of Representatives intended to strengthen labor rights would extend organizing rights to gig workers and apply more stringent tests to determine employment versus contractor status for workers.

Such efforts to strengthen protections for gig workers are admirable. They are, however, wrongheaded and would represent a Pyrrhic victory, especially when it comes to healthcare benefits access and delivery. One need look no further than our healthcare system, and employers’ failed efforts to reform it, to understand why.

Disruption, Disrupted

Just last month, Haven, the non-profit formed by Berkshire Hathaway, JP Morgan and Amazon, announced it was closing its doors. The venture, announced in 2018 to much fanfare, sought to utilize technology and the combined market power of its three founders to make healthcare work better for the companies’ combined 1.5 million employees. Reactions to the recent news from industry insiders ranged from assessing what went wrong, to smug satisfaction (“who knew healthcare is so complex?”), to suggestions about how employers should be working with state and federal policymakers and regulators.

Very few seemed to be questioning why Haven existed in the first place, or why JP Morgan, Berkshire Hathaway, Amazon and other employers are involved in healthcare decisions at all.

A System Nobody Would Design...

If we were designing a healthcare system from the ground up, who would suggest employers should play a critical role? ANDREY POPOV - STOCK.ADOBE.COM

Imagine sitting at a table with the nation’s best and brightest, trying to design a healthcare system from scratch. Medical doctors, health policy researchers, economists, patient advocates, bioethicists, public health experts, healthcare administrators, pharmaceutical executives, technology leaders and serious-minded policymakers from both sides of the aisle. All having an intellectually honest discussion - even a debate - about the key considerations that should be factored in. One could imagine the types of questions that might come up:

“How do we build health equity and accountability into the system?”

“How should we think about balancing individual rights with policies that benefit the population as a whole?”

“What is the right way to leverage market forces to manage costs while recognizing that economic efficiency may not be the right framework for dealing with certain healthcare decisions such as end of life care plans?”

“How do we leverage technology to enable quality reporting and improvement programs while not burdening clinicians who just want to provide care?”

If designing a system from scratch, one could imagine medical doctors advocating for the primacy of the doctor-patient relationship; or the economist’s focus on costs above all else; or the public health expert placing emphasis on social spending on social determinants of health.

What is it very hard to imagine? Anybody making the case that a person’s employer should play a critical role in that person’s healthcare decisions. Or, for that matter, that employers should play any role in healthcare whatsoever.

In fact, it’s unclear that anyone ever actually made the case that employers should be involved in healthcare decisions.

...Because Nobody Designed It

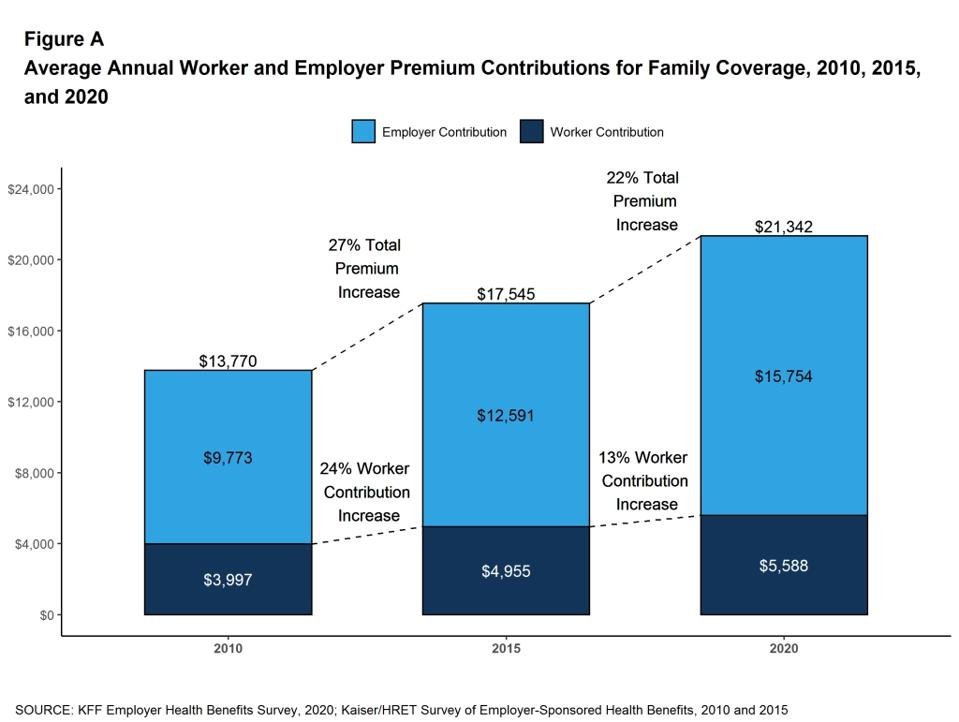

Most Americans today (162 million) - and the vast majority of working-age people - have employer-based health insurance. That is, most Americans rely on their (or their parents’) employers for access to health insurance. This is a critical benefit for people, as the total cost of insurance for a single employee has increased to $21,342, up from $13,770 just ten years ago.

KFF Employer Health benefits Survey, 2020. KAISER FAMILY FOUNDATION

But why do employers provide health insurance in the first place?

In fact, health insurance as we know it today did not really exist before World War II; hospitals originally began offering insurance themselves during the Great Depression as a way to generate more reliable revenue.

Our employer-based system today is the result of an odd situation stemming from an executive order by Franklin Delano Roosevelt during World War II to stabilize wage rates during labor shortages, and subsequently enshrined in tax policy and code, which allowed employers to recognize spend on health insurance as tax deductible (thereby reducing their taxable income).

As employers competed for labor, they increasingly turned to generous health insurance benefits to attract workers. This worked for both sides due to the tax loophole; employers could deduct the expense of health insurance, which employees couldn’t do. It made simple economic sense.

No one person ever made the case that employers should play a role in healthcare. But as their role became more pervasive over time and people began to rely on the benefits, employers became inextricably linked to our healthcare system.

The problem? Employers are in the business of running their businesses and organizations, not in becoming experts in healthcare. And the introduction of employers into healthcare decisions has led to substantial negative effects for healthcare, employers themselves, the economy overall, and of course for people themselves.

Is this really a problem, though?

Bad For Healthcare, Bad for Business, Bad for the Economy, Bad For People

Employer-based health insurance is indeed a problem. Upon even a cursory analysis, it’s such a readily apparent problem - perhaps the biggest problem, for reasons explained below - that it’s curious it doesn’t draw more political attention. Perhaps because while it lies in plain sight, it’s covered up by easier targets that also are certainly problematic.

The easier targets?

A reimbursement system that is still largely fee-for-service (meaning we pay for care, not for health or outcomes).

A lack of price transparency for services and healthcare products (such as drugs).

The high prices of services

Enormous levels of waste, fraud and abuse

Administrative complexity due to high levels of fragmentation

Monopolistic pricing practices of dominant health systems

There is data to support the case for each of the above. However, each obscures the broader and more systematic root problem: fragmentation exists, complexity exists, and waste and abuse is exacerbated, because the majority of Americans obtain their health insurance through hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of employers, which is:

Bad For Healthcare

For all the talk about "consumerism" trends in healthcare, we cannot truly empower people if they don't have a say in major healthcare benefit design choices. TS - STOCK.ADOBE.COM

First, the presence of employers as the procurers of health insurance creates an additional layer between consumers of care and the administrators of care (health plans). Even employers wishing to act truly in a benevolent manner and make broad benefit decisions that reflect their employees’ preferences as a whole still merely masks and distorts individual preferences, or prevents them from materializing at all.

For instance, the tax advantages of employer-based health insurance has led to employers competing for labor in part on offering so-called ‘Cadillac’ plans which individuals may appreciate but would be unwilling to spend if they were spending their own money.

Further, employers have different incentives than any individual employee; they may wish to be generous with coverage decisions but simultaneously manage costs, resulting in utilization management programs such as prior authorizations that frustrate patients and doctors alike. For advocates of ‘consumer-driven healthcare’ and ‘consumerism’ as a driver of change, the presence of employers simply adds a layer of inertia that confuses and obfuscates consumer signals.

Beyond this, the role of employers as a financing mechanism for health insurance contributes significantly to the problems described above (‘easier targets’): with more than 300,000 employers in the country with 50 or more employees, there is tremendous fragmentation in purchasing power, and high variability in terms of perceived needs. This creates a principal-agent problem: to win business, health plans may cater to individual employer needs in ways that prevent their effectiveness at a systemic level. For instance, employers in a given region may believe it important to include a well-known hospital their network and require their health plans to do so, regardless of (i) the health plans’ superior knowledge about the quality of care that the hospital provides and (ii) the adverse impact that this has on the plans’ ability to negotiate lower rates on behalf of the employer and members.

Finally, there are some who argue that employers serve as aggregators of individual health risk, which reduces financial risk and results in increased purchasing power. This is backward thinking. In fact, an employer’s size is a function of its effectiveness in a specific functional area or market position, having nothing to do with its effectiveness in aggregating its employees’ health risk. This creates arbitrary risk pools, and further confuses aggregation of risk at a micro level with that which is possible (and done) at a macro level, whether across employers or individuals.

Bad For Business

Corporate America rejoiced with the passage of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which reduced the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. One analysis suggested that the reduced tax burden would lead to significant business growth, which would lead to increased worker wages and more than 339,000 jobs created.

If a maginal reduction in the $327 billion paid in corporate income tax unleashed that much economic activity, just imagine what would happen if US businesses were freed from a health insurance burden that at $1.1 Trillion is almost four times the magnitude of income taxes.

Health insurance is the most expensive benefit that employers provide, and one of the fastest growing. It puts US businesses that compete on a global scale at a cost disadvantage, and costs consumers, too: General Motors has estimated that health insurance costs add $1,500 to $2,000 to the sticker price of its automobiles.

The inclusion of health insurance as a benefit can shift the calculus on individual and group hiring decisions: with healthcare costs of ~$21,000 per employee, staffing budgets do not stretch nearly as far, leading to fewer hires and making each hiring decision that much more critical.

Bad For People

The most obvious challenge of employer-based health insurance is that it results in job lock. At a high level, job lock in this context refers to a situation in which a person may want to leave her job, but is concerned with the need to secure health insurance from another source prior to doing so.

Employer-based insurance creates job lock and reduces choices, putting control in the hands of employers rather than people. It's hard to empower people as consumers if they aren't allowed to make benefit decisions. SEWCREAM - STOCK.ADOBE.COM

While proving out the job lock effect has proven difficult via rigorous studies, what is not difficult to recognize: a majority of Americans are concerned about being able to afford surprise medical bills. Job lock may also play a role in declining levels of entrepreneurship and new business creation in the United States.

Employment-based health insurance also arbitrarily restricts choice for people, placing benefit design and some downstream healthcare decisions in the hands of employers rather than individuals.

Bad For Society And The Economy

Job lock isn’t merely an individual problem (although it frequently is), but in aggregate leads to reduced economic dynamism. This problem is exacerbated by unnecessary burdens on business that force them to spend on non-core activities rather than those that can drive growth.

Add in the fact that employers are put in a position to make healthcare benefit decisions for their staff - when those two sides’ views on healthcare and religion conflict - and it adds to the absurdity.

Employer-based health insurance creates a vicious cycle for people, businesses, the healthcare system, and the economy. SERGEY NIVENS - STOCK.ADOBE.COM

Businesses have less capital to hire workers. Individuals have fewer job options, and are less likely to leave their jobs to start their own job-creating ventures due to medical concerns. The dysfunctional status quo leads to higher healthcare costs for businesses to bear. Businesses restrict options. Outsiders question why an employer is restricting access to healthcare and “buycott” the business.

It’s a vicious cycle.

Stop The Insanity: Why Haven Failed

It’s time to start looking beneath the surface, beneath the problems that most analysts can agree on, to identify the root causes of the sclerosis. With healthcare spend quadrupling on a per capita basis from 1980 to 2018, plus the well-documented dearth of value delivered from that spend, the time to look under the hood is nigh, and the disintegration of Haven provides perhaps the perfect case study to do so.

Haven was started by three of the largest, most sophisticated, most well respected and well-run corporations in the United States to help them break free of ever-rising healthcare costs. The three companies represented the collective purchasing power of more than 1.5 million employees, and they recruited an extraordinary team, led by surgeon and healthcare expert Atul Gawande. Yet Haven shut down just over two years of founding. Haven wasn’t the only employer coalition to take on healthcare

One of the more thoughtful takes summed up Haven’s challenge well: “Each company [Amazon, JPMorgan, Berkshire Hathaway] is different, based on the industry they’re in or their economic position. Think about it this way. If you’re going to move the needle with a standardized benefit design, there might be something that one employer in the group won’t give up.”

If Haven - backed by Amazon, JP Morgan, and Berkshire Hathaway - couldn’t get its three founders aligned and able to leverage their scale to bring down healthcare costs, is there any chance that 300,000+ employers will be able to? Unlikely, even if they form coalitions similar to Haven’s.

Perhaps politicians on both sides of the aisle should stop expecting them to. Further, the existence of the patchwork employer-based system creates inertia to systemic change and progress that could be made on other fronts.

In fact, there are clear wins for liberal groups and conservatives if they can look past the current model of employer-based health insurance. The answer seems inevitable; it’s just a matter of how long it will take for each side to gather the political will and courage to embrace it.

Platforms And The Gig Economy Are The Answer

Contrary to the picture of the gig economy as “precarious work”, the vast majority of gig workers engage in the work by choice. The gig economy offers attractions to workers that traditional employers have difficulty in matching, including a high degree of autonomy (which tasks or projects they accept and the timing of that work), financial upside, choice of working style, and greater flexibility of relationships.

The gig economy is also expected to expand in the coming years, again largely by choice. Platforms such as Upwork are expanding the type of work that can be done via the gig economy to include more skilled service jobs, matching available freelancers to businesses that have project needs. And additional infrastructure platforms are emerging to help support gig workers and freelancers, providing them tools to optimize their earnings and helping them to plan.

Services such as Upwork are good for businesses, too: they allow employers to quickly find talented freelancers and uncover at a low cost the quality of their work. Such an iterative process can turn an uncertain, costly and fraught-filled recruiting and hiring process into an easier, lower cost way to test out new relationships.

The policy considerations: at some point in the near future, we are likely to reach a time at which the number of gig workers and freelancers creates a tipping point effect in labor markets. Already, there are legitimate questions about how to provide a safety net for gig workers.

Politicians face a choice: repeat the failed policies of the past and saddle platforms businesses like DoorDash and Upwork with employer obligations - which would negatively impact their business models and slow their growth - or embrace the future.

For Democrats, more gig economy workers creates a larger constituency who will likely need and vote for social safety net programs such as a public option or Medicare For All. In addition, health insurance exchanges, created by the Affordable Care Act, are direct-to-consumer platforms that have proved to be a valuable, essential tool for the millions of eligible enrollees who need to secure coverage on their own, as opposed to going through an employer or a government-run program like Medicare or Medicaid. The federal and state-run exchanges promote plan competition and choice by allowing consumers to compare and shop for coverage on their own, as well as obtain premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions, which serve to reduce premiums and out-of-pocket costs.

For Republicans, more gig workers means better functioning job and labor markets, reduced corporate cost burden and improved global competitive position, and improved economic dynamism and growth.

To be sure, the devil is in the details. But embracing the future, and reducing the burden on employers, isn’t even a radical idea, nor is it partisan: the bipartisan Healthy Americans Act in 2007 proposed shifting from the existing employer-based to individually procured plans from state-based exchanges. An independent analysis concluded that it would have achieved universal coverage, and would be self-financing after its first year, gradually bringing down costs.

“Never Let A Crisis Go To Waste”

Rahm Emmanuel recently reprised his famous line, “Never let a crisis go to waste,” which is incredibly fitting given the once-in-a-lifetime pandemic we’re all living through. Rather than fight for Pyrrhic political victories (as was Bunker Hill for the British) by burdening more employers with benefits, we need to look at the root cause of the inequities and inefficiencies in our healthcare system, take aim at the right targets, and shoot with purpose.

To invest in a better future requires a commitment to growth and change and an unapologetic questioning of the status quo. Employer-sponsored healthcare isn’t working, and no number of care navigator companies or employer-focused solutions will fix that fact.

The rise of the gig economy and utility of platforms represent a new, strategic path forward for healthcare delivery and benefits administration in the US, and ultimately can provide an exit ramp for this country’s 75-year history of failure of employer-sponsored health insurance.

Continue the conversation with Seth Joseph at seth@summithealth.io